Discovering Curiosity: Building Mini-Organs to Fight Pancreatic Cancer with New Faculty Chang-il Hwang

Quick Summary

- Pancreatic cancer accounts for 3% of cancers nationwide, but 91% of patients succumb to it within five years of diagnosis

- Hwang developed miniature organ models to study pancreatic cancer from its earliest stages

- By tweaking biological pathways within cancer cells, Hwang hopes to make them more susceptible to therapies

When a healthy cell turns cancerous a cascade of events enables the cancer to spread throughout the body. But its origin lies within a single progenitor cell.

“What goes wrong with that particular cell?” asked Assistant Professor Chang-il Hwang, Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics. “Something happens at the molecular level. One DNA molecule, or one protein molecule changes.”

Those changes can have a butterfly effect that endangers the entire organism.

Hwang studies pancreatic cancer, one of deadliest cancers. While it only accounts for 3 percent of cancers nationwide, 91 percent of patients succumb to the illness within five years of diagnosis. The problem is compounded because pancreatic cancer isn’t detectable until its late stages, when it’s spread to other organs. Since the pancreas is situated deep in the abdomen, tumors often escape detection, and physical symptoms usually don’t manifest until it’s too late. Recently, Jeopardy host Alex Trebek announced that he was diagnosed with stage IV pancreatic cancer.

“We know a lot about the histopathology and the genetics of pancreatic cancer but we don’t have a good ability to detect it early on,” said Hwang.

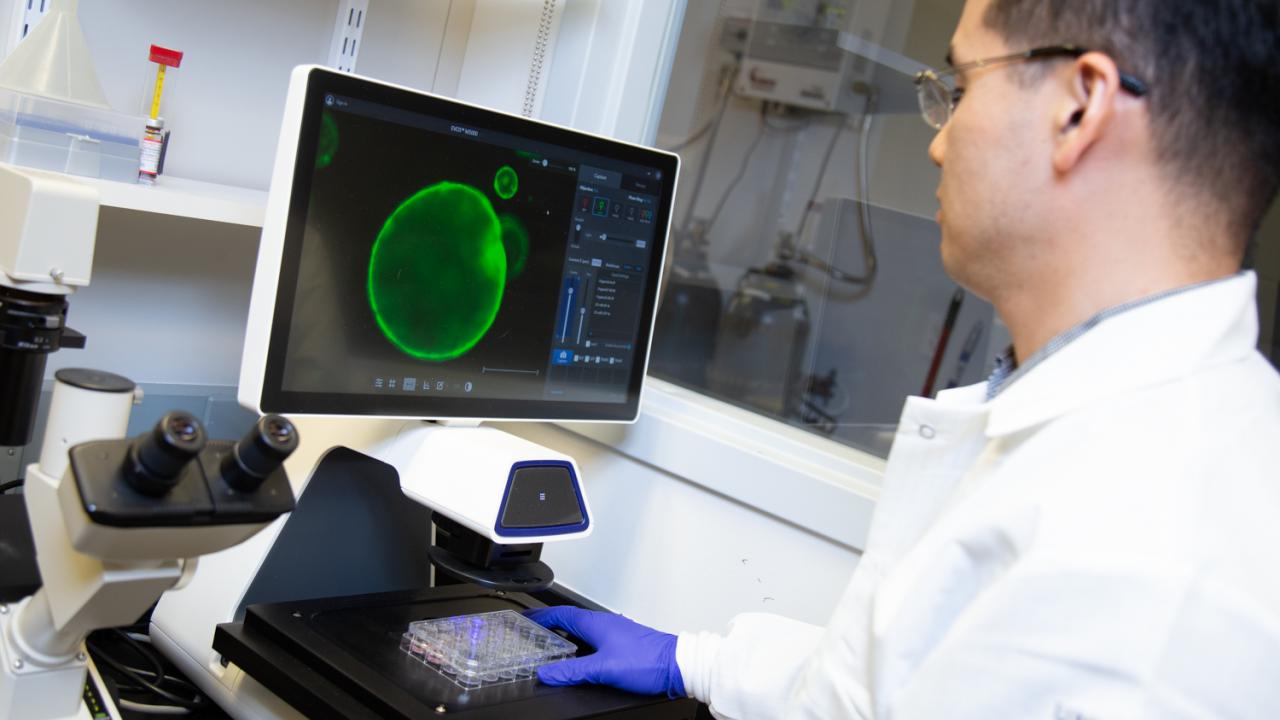

On the hunt for methods to aid early detection and better therapeutic treatments, Hwang developed pancreatic cancer organoids, miniature organ models that allow him to study pancreatic cancer from its earliest stages. Today, he uses them to help advance basic and clinical research at UC Davis.

“In a tissue culture system, we can ask a lot of questions,” said Hwang. “What drugs work out? What is the mechanism behind it?”

Hwang can then verify those findings by transplanting the organoids back into mice. It then becomes easier to apply those discoveries to humans.

Superhero scientists

Hwang grew up in Seoul, South Korea and was inspired to become a scientist by the fictitious Kōzaburō Nambu, a character on the Japanese cartoon show Science Ninja Team Gatchaman. The fantastical series follows a five-person superhero team as they battle monsters threatening Earth. Behind the superheroes is Nambu, a scientist providing the team with technological support.

“I wanted to be that kind of scientist,” recalled Hwang of his childhood ambition.

After high school, Hwang took advice from one of his high school biology teachers and decided to enroll in pre-veterinary courses due to the field’s growth in South Korea. Hwang tailed the vet med track and eventually earned a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degree from Seoul National University. But he was unsure if he wanted to pursue a career as a clinician. He was drawn to lab work and molecular biology, an interest spurred following an undergraduate biology course.

“I loved those classes,” said Hwang, noting he was awed by the growing capability to structurally define molecular interactions within cells.

“We could see the action and we could figure out the mechanisms,” he added. “We could explain disease and we could explain how drugs work for certain diseases.”

Developing mini-organs

Hwang returned to academia, earning another master’s degree in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at Seoul National University and then completing a Ph.D. in Comparative Biomedical Sciences at Cornell University, where he studied the genetics behind ovarian and breast cancers in mouse models.

“I wanted to challenge myself to study hard cancer types,” said Hwang.

He then accepted a postdoctoral position at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y. According to Hwang, the lab he joined primarily focused on studying cancers in mouse models, but a shift was in the midst.

In the Netherlands, researcher Hans Clevers, of the Hubrecht Institute and Utrecht University, had developed mini-organ models. Grown from the cells of patients, these organoids can help researchers track disease development and help them develop and identify patient-specific therapies for those diseases. The organoids, comprised of hundreds of thousands of cells, are microscopic in size and look like hollow spheres.

“Hans Clevers and his group’s interest was to develop an organoid to try to differentiate organoid cells into insulin-secreting cells for diabetes research purposes,” said Hwang. “But in our perspective, we thought that this organoid model could be a really useful platform to study pancreatic cancer.”

A collaboration was born and soon, Hwang and his colleagues were figuring out ways to grow healthy epithelial cells, the linings of the pancreatic ducts, with the intent of studying them as they turned cancerous.

“The beauty of organoid culture is that we can grow those normal cells and study really all the events of pancreatic cancer progression,” said Hwang, adding that his team can grow a patient-derived organoid with a success rate of about 75 percent.

Creating avatars for cancer

After a successful organoid is grown, researchers can then test various drugs and different combinations on it to see which one a patient might respond to best. The robustness of the treatment can then be tested on mouse models with pancreatic tumors, which can be designed to retain the genetic information of the human patient. “It’s kind of an avatar model,” said Hwang.

At UC Davis, Hwang is continuing his pancreatic cancer research and exploration of organoids. Currently, he and his lab colleagues are interested in metastatic pancreatic cancers, which eventually spread to other organs in the body, like the liver and lungs.

“We have tons of collaboration with the UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center, so they provide the patient samples,” said Hwang. “We try to grow them up as organoids and then study what’s going on.”

By tweaking biological pathways within cancerous cells, Hwang hopes he and his team can manipulate the cells to be more susceptible to therapies that previously didn’t work.

“We need to find better therapeutic treatments and strategies for those patients,” said Hwang.