Blending In: Ecology Graduate Student Grace Ha Investigates Camouflage in Seagrass Meadows

Quick Summary

- Grace Ha is an ecology graduate student studying camouflage in seagrass beds

- Seagrass beds are known to be nurseries for juvenile marine organisms

- Ha performs field experiments to understand the survival rates of prey species in different colored habitats

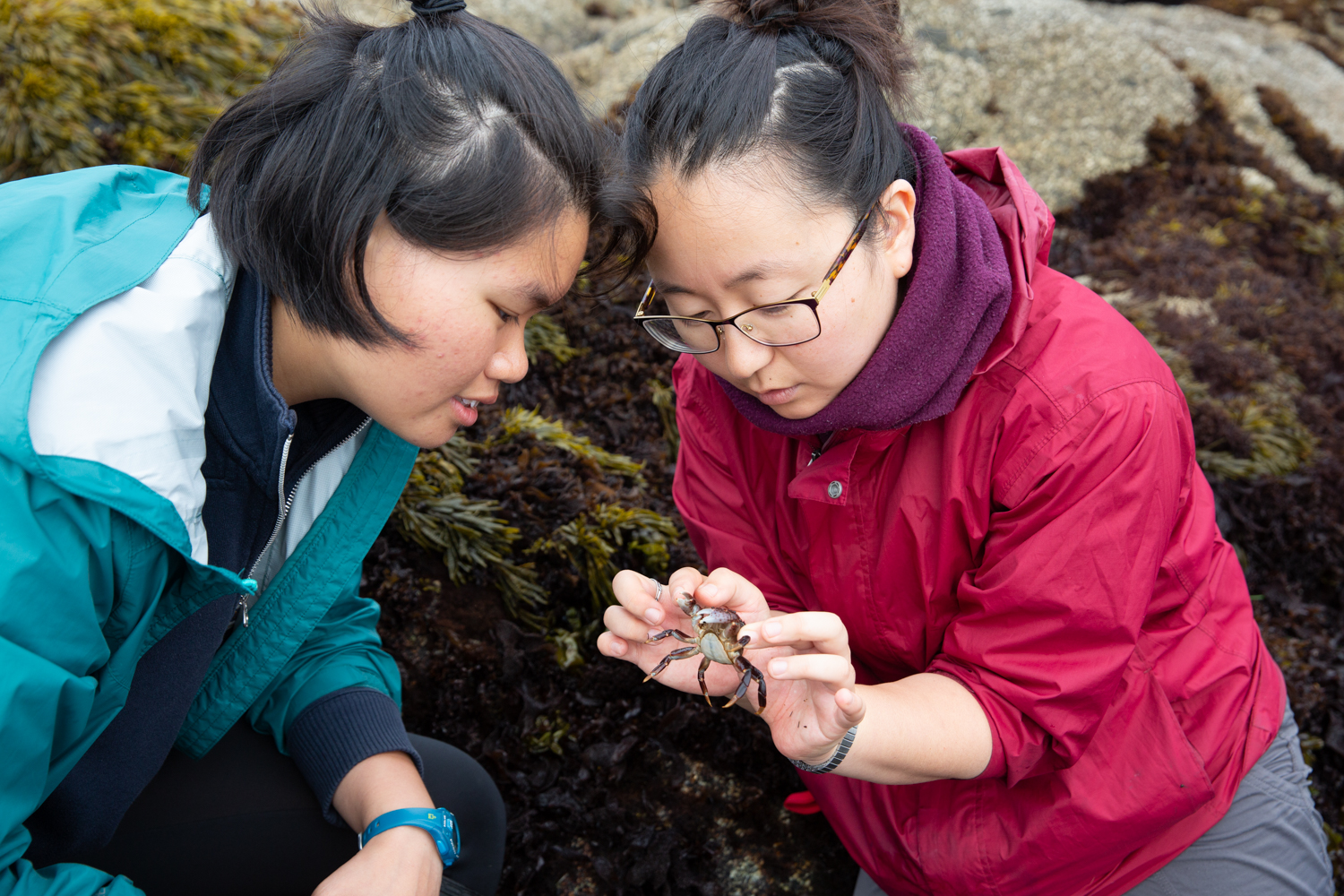

Morning fog hugs Horseshoe Cove, a wispy veil of gray masking the Pacific Ocean. As it rolls towards the beach by the Bodega Marine Laboratory, UC Davis students explore the cove’s tide pools. A sea star engages in a slow motion life-or-death battle with a mussel, a bright yellow nudibranch traverses a kelp blade and a quarter-sized crab scurries among wet rocks.

“We’re in a region with a Mediterranean climate and upwelling— what’s cool is that both of these are associated with high levels of biodiversity,” says Grace Ha, an ecology Ph.D. student. In upwelling zones, nutrient-rich waters from the deep ocean are transported to coastal regions, which makes them hotspots for biodiversity.

As Ha guides the group to the intertidal zone, she discusses the three subset zones within it. Mid-explanation, she stops and turns to the group of undergraduates, all of whom were at the Bodega Marine Laboratory for summer classes.

“You guys are taking the class,” Ha says and turns to Stephanie Tsui, a senior environmental science and management major. “Can you explain zonation?”

Tsui smiles. “The tidal height affects how much a certain area is submerged throughout the day, so there’s the low, middle and upper intertidal zone,” she says. “Because the lower intertidal zone is submerged more, there’s usually more biodiversity and as you get higher, it’s more stressful for marine species because they’re more exposed to the air and desiccation. So there tend to be fewer species living there.”

Though Ha leads the impromptu tour of Horseshoe Cove, her research actually relates to a different habitat. Ha studies seagrass beds, specifically beds of eelgrass (Zostera marina).

“Eelgrass is an unsung hero of coastal zones,” says Ha. “It forms meadows -- beautiful, lush meadows underwater that host a wide diversity of species.”

Since enrolling at UC Davis, Ha has studied eelgrass through the lenses of ecology and natural history. She currently researches the role camouflage plays in these beds.

“I spent a lot of time characterizing this ecosystem and the species in it,” says Ha. “Over the course of that work, I became fascinated by how everything was green—the habitat, the crustaceans, the worms, the anemones, the slugs, even some of the fish. Why was everything green?”

Learning to see marine ecology

Ha didn’t consider marine ecology as an academic pursuit until her sophomore year at Cornell University. Already on the premed track, she wanted to enroll in a class that was completely different than any she’d taken before. One day, she found a flyer on campus advertising a field class in marine biology at the Shoals Marine Laboratory in Maine, which is jointly run by Cornell and the University of New Hampshire.

“It was a class that involved waking up early in the morning for the low tide and coming out into the field to the rocky intertidal,” says Ha. “I had fantastic professors and their whole mission for us was to learn to see, and I think that was the biggest thing for me.”

Ha grew up outside of Philadelphia in Blue Bell, Penn. While she wasn’t particularly outdoorsy during her youth, she was enamored with the rugged, outdoorsy characters she read about in books. After experiencing research firsthand, she was hooked.

“I was obsessed and just took as many ecology classes as I could in my senior and junior year of college,” she says.

Finding inspiration from the late Susan Williams

After graduation, Ha spent a year in Korea on a Fulbright Scholarship, exploring intersections between anthropology, sociology and marine ecology. She returned to the U.S. with her sights set on graduate school, with the Bodega Marine Laboratory already on her radar. Eventually, she joined the lab of the late Susan Williams, whose research revealed how strategically planting seagrass beds could help restore marine environments damaged by human activity.

“I wish I could have heard more stories from her life — her colorful, difficult, incredible life — because through everything she experienced, it was an inspiration to see how she still retained an absolute passion for the ocean,” Ha recently wrote in a piece for Bay Nature Magazine. “What a privilege it was to have her as a role model and mentor.”

Ha intends to name a new species of crustacean she discovered after Williams.

Inside the disguised world of eelgrass

Seagrass beds are known to be nurseries for juvenile marine organisms, like crustaceans, smelts, and anchovies. With so much green, one might assume it’s beneficial for prey species to be similar in color to their surroundings.

“Camouflage is something children learn starting from a young age, and it’s an engrained part of how we think about ecology and evolution,” says Ha, noting that the idea of camouflage is really about predation.

The theory typically goes that the less detectable the prey species, the more likely it will survive and pass on its genes to the next generation. But camouflage, according to Ha, is much more complex.

Ha works with a bright green, shrimp-like crustacean called Ampithoe lacertosa, performing field experiments to understand their survival rates in different colored habitats. So far, her data indicates that in seagrass environments abundant with predators, the match between the color of the crustacean and its habitat doesn’t seem to matter. Camouflaged or not, they get gobbled up. Ha says this makes sense since a high abundance of predators likely means there’s a high variety of visual capabilities among the predator population.

“Color, if you think of it technically, is not an intrinsic trait of an object; it is the perception of that object by a viewer.” says Ha. “The context in which we see a particular color really affects how we see that color itself.”

While people have written about camouflage as a theory, Ha says the relative lack of experimental research motivated much of her current work. Answering such deep questions about color and camouflage will require further investigations that combine ecology and neurobiology, according to her.