Fusion of Science and Parenting is Focus of Professor's Research, Advocacy and Art

Being a parent can be stressful.

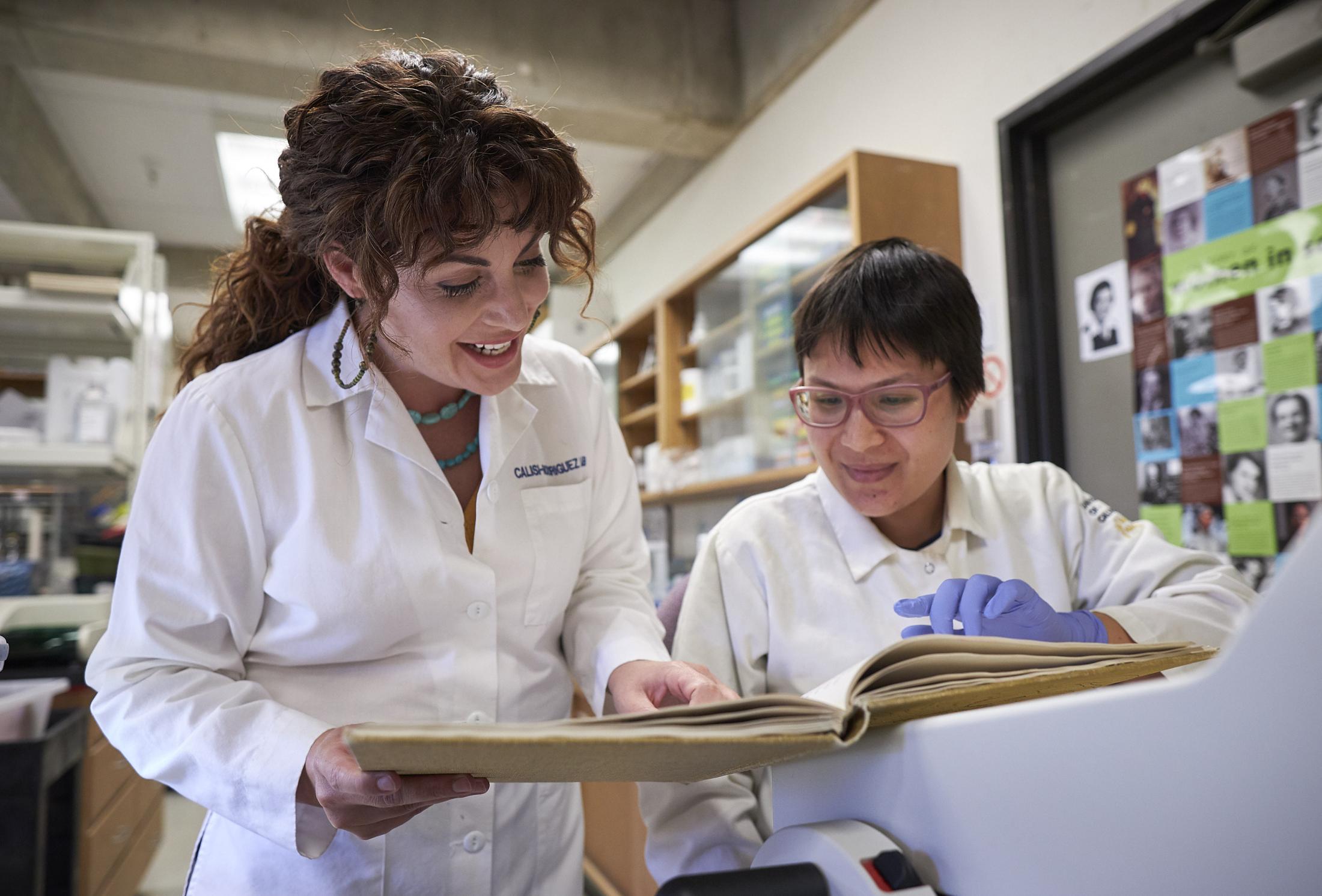

For Associate Professor Rebecca Calisi Rodríguez, parental behavior has inspired her research as a biological scientist, as well as her public advocacy message.

Calisi Rodríguez studies the hormonal shifts that occur in numerous species because of parental instincts. She also is passionate about encouraging the scientific community to be more supportive and accepting of diversity in STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) careers, especially for those who are mothers.

“In order to support science, we must support the diverse needs of the people doing the science,” she said. “I’m really interested in creating inclusive cultures in academia and making sure that people can bring their authentic selves to their work, which will enhance the research community.”

Bringing a diverse past and perspective to science

The genesis of Calisi Rodríguez’s career started when she was a little girl on her family's ranch near the Texas-Mexico border. There, Calisi Rodríguez spent her summers in pastures where her family raised Santa Gertrudis cattle—a breed that is used both for dairy and meat production, and that can withstand the heat of Texas summers.

“So I had my first lessons in physiology, genetics, stress and reproduction—all the things I study and base my research projects on now—back then on the ranch,” Calisi Rodríguez said. “I didn’t realize it then, but I realize it now—that was where I became interested in animals and it created this foundation of curiosity in me.”

That curiosity, however, did not lead her directly to a career in the sciences. Instead, she took a more circuitous route. For her bachelor’s degree, Calisi Rodríguez pursued a degree in art. It was through art that she found her calling in science.

It happened during one of her first jobs when she was commissioned by the Dallas Zoo to paint a large mural of African animals. While at the zoo, Calisi Rodríguez volunteered to help with an experiment the zoo was conducting to determine why the okapi, zebra-like relatives of giraffes, weren’t breeding. Calisi Rodríguez’s job was to collect urine samples. Those samples revealed that the okapi had extremely high levels of the stress hormone cortisol in their system. Staff at the zoo removed all possible stressors from their environment and, about a month later, the okapi started breeding again.

“To me this was huge. I like to call it my Dr. Doolittle moment because, in a way, the okapi were talking to us,” she said. “They were telling us through their hormones that they were really stressed out.”

Transformed by this experience, Calisi Rodríguez decided to pursue a graduate degree in biology where she said she found “the perfect animal to help us unravel the mysteries of parental care behavior.” That animal was the pigeon.

“Why pigeons are so exciting is because both mom and dad care for the babies and, my favorite part, both mom and dad do something that is very rare for birds—they lactate!” Calisi Rodríguez said excitedly.

Milking positive change

Pigeons create a crop milk that is stored in a sac behind their throats and is fed to the babies during the first few days of life. The process is driven by prolactin, which is the same hormone that activates lactation process in mammals, including humans.

“Because both the mother and father produce milk, we were able to gain clearer insight into the factors that trigger lactation, beyond those that are specific to females,” Calisi Rodríguez said. “That’s why this is such a powerful model.”

Lactation was also the impetus for Calisi Rodríguez’s advocacy within the scientific community. It started when Calisi Rodríguez, who was a new mother, attended an all-day conference to help her network and advance her career as a junior researcher. When it came time for the breastfeeding mother to pump, Calisi Rodríguez was disappointed to find the lactation facility at the conference was nothing more than a three-curtain covered area and one metal chair. She took to social media to help raise awareness on the issue. Since that day in 2018, she has written numerous pieces on the difficulties of breastfeeding in the workplace, postpartum depression, and childcare. Her work has spurred positive outreach by many female scientists and helped many major conferences improve their facilities for lactating mothers.

“Some people may not understand why I made such a big deal about supporting lactating mothers at conferences, but it’s a metaphor of how we are treated in general,” she said. “If we can’t support women in those circumstances, then we are going to lose them. If we lose them, then we are losing diversity at the table and we are losing potential solutions and cures in our future.”

Engagement through creative expression

Since then Calisi Rodríguez’s a scientific communicator. She founded a production company called Calisi Productions, through which she has created numerous films focused on supporting diversity and inclusion in the sciences. She also created a video series in partnership with UC Davis called “I Can Science” with funding from National Geographic.

During the pandemic, Calisi Rodríguez was inspired to tap into her talents as an artist to create a poignant, collage-like, illustration called “Essential Work” that explores some of the stresses created by the pandemic, which ran in the January 16, 2022 issue of the Los Angeles Times.

“I had been working on this piece since the start of the pandemic, when I was moved by stories of healthcare workers, lacking medical supplies and suited up in trash bags, risking their lives for us,” Calisi Rodríguez said. “It was a form of therapy for me—a way to help me process what was happening. As time went on, I continued to draw images from stories that moved me. Recently, an editor from the LA Times contacted me and asked if I could contribute a piece about my experience as a mom in science during this time. I handed this drawing right over to him.”

Included in the mural are images of a woman with an Asian-American child who is crying and holding a hand-drawn sign that reads “I am not a virus,” a screaming white man whose bald head is being doused with hand sanitizer, and a scientist’s apple watch, which says, “Your child’s school district has switched to remote learning. Again. Your career is toast. P.S. Pick up more antidepressants.” Calisi Rodríguez says each image was intended to illustrate the myriad issues the public scholarship community has been trying to manage since 2020.

“Here we are as scientists, trying to help increase public knowledge, understanding, and safety, all the while lacking the support we need to actually do our jobs,” she said. “Everyone loses in this situation.”

Calisi Rodríguez says she is motivated to put herself out there as a Mexican-Italian-American woman, professor, artist, communicator, dancer and mother who has struggles because she wants others to realize they can be their true, authentic selves and pursue a career in the sciences.

“I think it’s really important to show our next generation of scientists that we’re human,” Calisi Rodríguez said. “That’s my motivation: standing up for a more inclusive culture in STEM, because it brings our authentic selves and experiences to the table and that's how we change the world.”